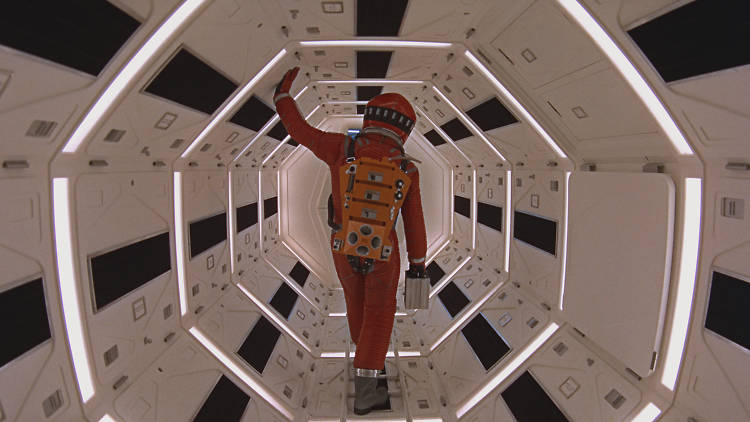

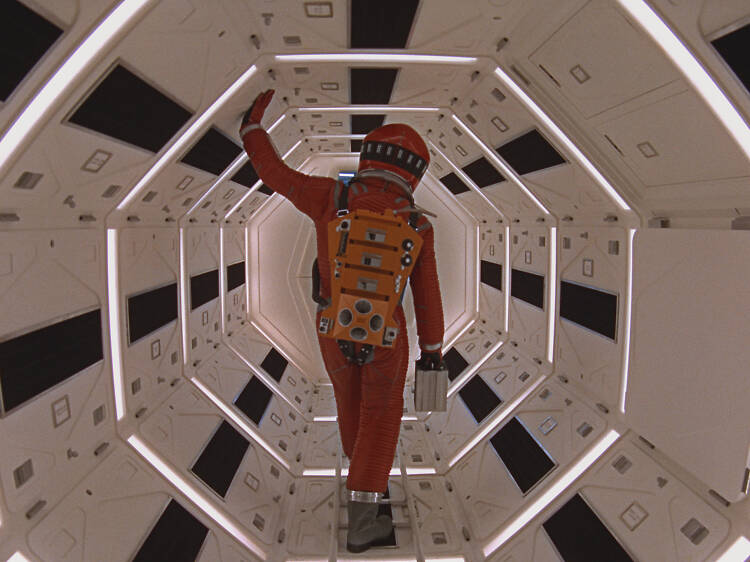

The greatest film ever made began with the meeting of two brilliant minds: Stanley Kubrick and sci-fi seer Arthur C Clarke. ‘I understand he’s a nut who lives in a tree in India somewhere,’ noted Kubrick when Clarke’s name came up – along with those of Isaac Asimov, Robert A Heinlein and Ray Bradbury – as a possible writer for his planned sci-fi epic. Clarke was actually living in Ceylon (not in India, or a tree), but the pair met, hit it off, and forged a story of technological progress and disaster (hello, HAL) that’s steeped in humanity, in all its brilliance, weakness, courage and mad ambition. An audience of stoners, wowed by its eye-candy Star Gate sequence and pioneering visuals, adopted it as a pet movie. Were it not for them, 2001 might have faded into obscurity, but it’s hard to imagine it would have stayed there. Kubrick’s frighteningly clinical vision of the future – AI and all – still feels prophetic, more than 50 years on.—Phil de Semlyen

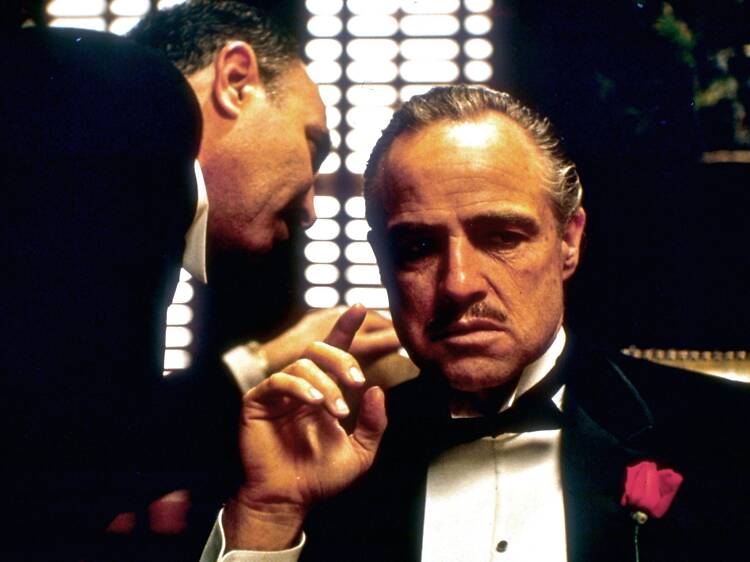

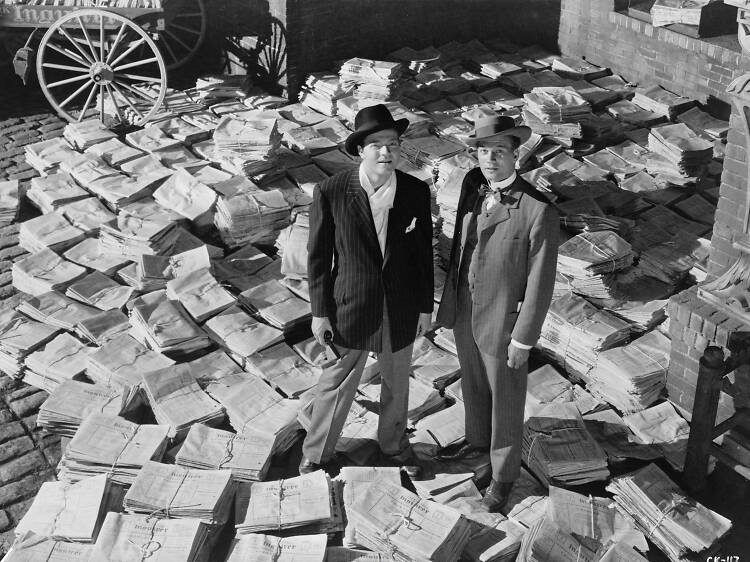

In media, a list is a powder keg waiting to explode the moment it’s published, especially if it’s called something like ‘the 100 greatest movies ever made’. If you’re passionate about something, you’re going to feel compelled to fiercely defend your favourites and shout down whatever you think is undeserving. If we’re being honest, inflaming public discussion is one of the reasons anyone decides to do a project like this. Debate gets you thinking, and, when reasoned and civil enough, perhaps even rethinking.

But don’t think of this as an attempt to shove our opinions down your throat. We consider this list more of a reference manual: a jumping off point for anyone looking to fill in the gaps of their movie knowledge – or, for more advanced cinephiles, a way to challenge their own preconceived notions. After all, we cover a lot of ground here: over 100 years, multiple countries, and just about every genre imaginable, from massive blockbusters to cult films, comedies to horror, thrillers to action flicks.

Written by Abbey Bender, Dave Calhoun, Phil de Semlyen, Bilge Ebiri, Ian Freer, Stephen Garrett, Tomris Laffly, Joshua Rothkopf, Anna Smith and Matthew Singer

Recommended:

🔥 The best films of 2024 (so far)

🏆 The 100 greatest horror films ever made

📺 The 100 greatest ever TV shows you need to binge

🤣 The best funny films of all-time